One Friday night in June, with the residence halls empty and the U-M campus eerily calm, one place still rocked: The library. No, seriously.

In one corner, a couple of kids searched for the zombie cure in “Dark Souls II” on a PlayStation 4. Near them, on an Xbox 360, some friends used “Fight Night Round 3” to find out what it might have looked like if Ali had fought De La Hoya. Elsewhere, a rowdy bunch on a Wii were beating the crap out of one another in a noisy game of “Super Smash Bros.,” while nearby on a desktop computer an online battle game of “Dota 2” was in progress. Meanwhile, a young woman sat at a table with an iPad trying to best the space-adventure app “ALONE.”

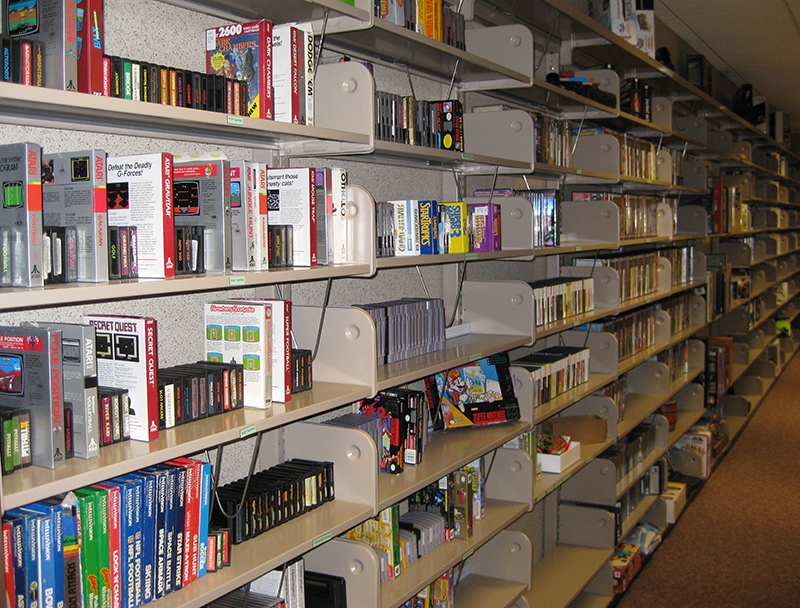

No bespectacled librarian hushed anyone at the Computer & Video Game Archive (CVGA), which may be the coolest repository of knowledge and information since the Egyptians invented the library. A 1,000-square-foot lair in the basement of U-M’s Duderstadt Center, the CVGA boasts nearly 8,000 video games that can be played—for free—on more than 60 consoles, from the classic Atari 2600 to the motion-sensing Xbox Kinect. Other video game archives have sprung up, notably at Stanford University and the Library of Congress, but they either are not as comprehensive or they don’t allow the public to play the games.

No bespectacled librarian hushed anyone at the Computer & Video Game Archive (CVGA), which may be the coolest repository of knowledge and information since the Egyptians invented the library. A 1,000-square-foot lair in the basement of U-M’s Duderstadt Center, the CVGA boasts nearly 8,000 video games that can be played—for free—on more than 60 consoles, from the classic Atari 2600 to the motion-sensing Xbox Kinect. Other video game archives have sprung up, notably at Stanford University and the Library of Congress, but they either are not as comprehensive or they don’t allow the public to play the games.

“A video game archive that is so serious that you can’t do anything but wear latex gloves to handle things carefully kind of misses the point,” says Mika LaVaque-Manty, a U-M political science professor who incorporates games into course material in the social sciences elective “The Games We Play.”

Indeed, that’s exactly what engineering librarian Dave Carter wanted to avoid when he founded the collection in 2008 based on an idea of art professor Phoebe Gloeckner. At that time, the collection had 20 games, a PS3, an Xbox, and an original Wii. “We wanted a space that collects games for academic purposes and also encourages people to use the games,” Carter says.

While Carter gets about $13,000 a year to acquire new materials, mostly the latest issues and systems, much of the CVGA’s growth has come from donors clearing out their garages of ancient e-junk. That’s how Carter says he landed such obscure systems as the short-lived, early-1980s cult favorite Vectrex and the once-hot-in-Japan GameBoy knockoff WonderSwan. The favorites of every era are here, from an original 1975 home “Pong” machine and the all-text adventure “Zork” to “Call of Duty” and “Candy Crush Saga.” Most popular? “FIFA,” Carter says, referring to the soccer game, “on any system we can get it for.” Currently, he has placed a Namco Pac-Man’s Arcade Party Cocktail Game Cabinet, valued at around $3,000, on the U-M Library’s online wish list, which is published for donors looking for a way to contribute.

As fun as the CVGA is, it serves many academic purposes. Engineering classes come by for lessons on programming and game design, but just as often it’s a variety of humanities classes that derive research value. In the fall 2018 semester alone, according to the CVGA site, the archive will factor into the syllabi of at least nine courses, including classes in comparative literature (zombie fiction), education (how video games aid learning), and screen arts and culture (adaptations of films to other media).

Lisa Nakamura, professor of American culture, relies heavily on the archive for a class tracing the evolution of representations of race, gender, and sexuality in video games. She says the perception that video games are unserious persists but is starting to fade. “There’s a really large appetite for this medium,” she says. “Reading literature is about storytelling in the same way that video games are.”

When Matthew Thompson, MMUS’06, AMusD’10, hosted the North American Conference on Video Game Music earlier this year, he took about 30 academics from around the world through the CVGA to wow them “because anybody could come here from anywhere and do some really good research.” Thompson, an assistant professor of music, says the CVGA is “one of the reasons that I have been so happy to be here.”

In fact, Gloeckner originated the idea for the collection because she wanted to teach about game design, history, and culture. “This is our cultural history,” says Gloeckner, author of the best-selling graphic novel “The Diary of a Teenage Girl.” She says video games are “a medium like any other, like painting, like literature. There’s the possibility of multiple masterpieces. It can do the same thing a novel does, take readers into another world and keep them there for however long it takes to tell a story.”

In fact, Gloeckner originated the idea for the collection because she wanted to teach about game design, history, and culture. “This is our cultural history,” says Gloeckner, author of the best-selling graphic novel “The Diary of a Teenage Girl.” She says video games are “a medium like any other, like painting, like literature. There’s the possibility of multiple masterpieces. It can do the same thing a novel does, take readers into another world and keep them there for however long it takes to tell a story.”

It’s also become a subversive recruitment tool. “We get really high-achieving students the engineering school wants,” Carter says. “They leave them with us for a half hour, let them get their hands on the controllers. It’s a definite selling point.”

The boom in games on mobile devices, which barely existed a decade ago when Carter launched the archive, is testing his ability to keep up. This, he says, will be his greatest challenge going forward because it requires maintaining collections of old phones and tablets and somehow archiving games that are not distributed through any physical media. “Keeping old mobile platforms with old operating systems running is the latest iteration of that challenge,” he says. “If a game stops being available, we potentially lose it if it is no longer available and the hardware it was downloaded onto was lost or damaged.”

If there’s a complaint about the CVGA, it’s that it’s so hidden and remote to most students that it’s “really, really an undervalued asset or underpublicized asset,” Nakamura says.

“It is a windowless, dark space, but video games are no longer a subculture of media that should be tucked away,” she says. “I wish more people knew about it, and it was in a more central and beautiful site. It’s definitely the happiest part of the library.”

Steve Friess is a Michigan-based freelance journalist and a 2011-12 Knight-Wallace Fellow at U-M. His work appears regularly in The New York Times, The New Republic, Playboy, and many others.