Andrea Joyce’s Golden Career

•

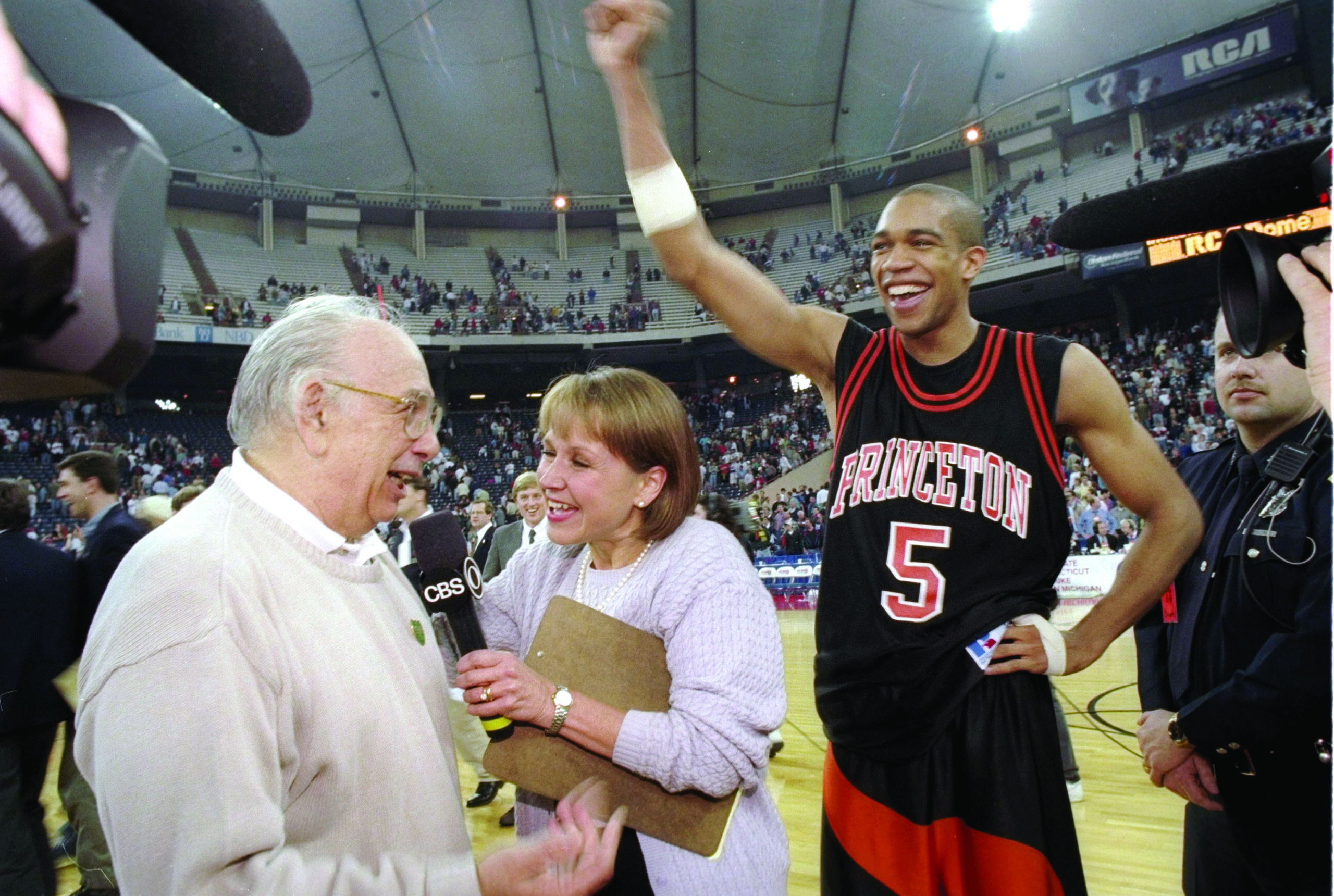

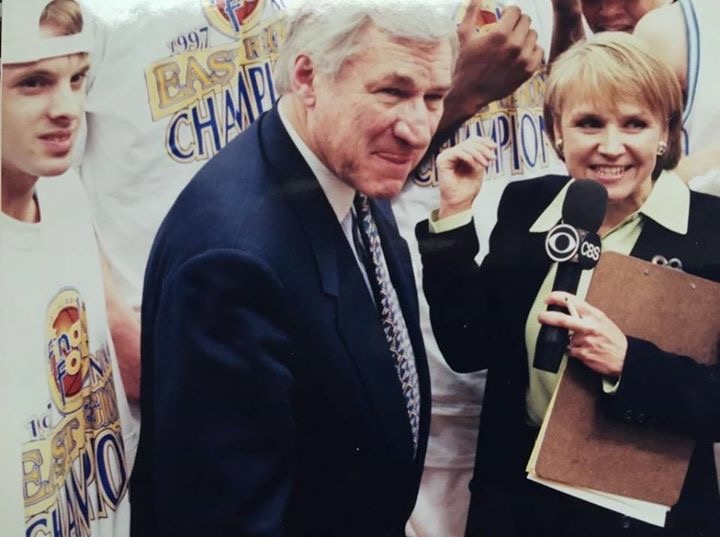

Photos courtesy of Andrea Joyce

Growing up in Michigan, Andrea Joyce, ’76, loved sports. She saw every Detroit Lions Thanksgiving game with her dad, uncle, and brothers. She was at Tiger Stadium when the Detroit Tigers clinched the pennant in 1968.

Joyce didn’t love sports just for the sake of the games. Sports, she says, were “part of the culture and part of the heartbeat of our society.”

But after graduating from the University of Michigan and starting her broadcasting career, she says she didn’t have “the luxury of dreaming” about being a sports reporter. At the time, there were very few jobs for women in newsrooms and even fewer in the sports department.

“You saw the movie ‘Anchorman’? You thought it was a comedy? It was a documentary,” Joyce recently joked during her induction into the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame about the misogynist nature of the business in the 1970s.

About a decade into her career, Joyce broke into sports broadcasting and covered the 1988 Olympic Summer Games in Seoul, South Korea as a reporter. Thus began a legendary career in sports which has included covering 16 Olympic Games for ESPN, CBS Sports, and NBC Sports.

As she prepares for what she says is likely her final Olympic Games this summer in Paris, Joyce says the awe of the event has not diminished over the years.

“You still feel like it’s this thing that’s bigger than you,” Joyce says. “It’s also this thing that brings everyone together. Any differences that you have just seem to melt away, and you’re all there cheering. A lot of these people train in obscurity their entire lives for this one moment. To be part of that — what a gift. It’s truly a gift.”

On Air, On Campus

Joyce came to Ann Arbor after spending her first year of college at UM-Dearborn and entered a different world.

“There was this atmosphere that your life can, and should, be anything but ordinary. It went from professors to friends to classmates. Across the board, you had that sense,” she says.

For Joyce, that sense didn’t immediately translate into her on-air career. In an early class, Joyce, a speech communication major, had to write and record a 30-second commercial in one take. She decided to do a spot for Swiss Miss instant cocoa. Everything was all set — the mug, the ski hat, the gloves.

Joyce got out the first line out, and blanked.

“And that,” she says, “was my first foray into television.”

Despite her inauspicious start, Joyce fell in love with the medium, producing and directing nonstop in Ann Arbor. She knew she possessed a performance gene and she loved to write but, at graduation, Joyce had no job prospects. A $500 scholarship to attend graduate school provided a reprieve but she left after a semester for her first on-air job in Colorado Springs as “the weather girl,” despite not being a meteorologist. With the unknown ahead, Joyce says U-M is what made her brave.

“I don’t remember being particularly nervous,” she says. “I thought I could do it. I was comfortable from the beginning, other than that first time. I credit [the University of] Michigan. It was that whole sense of you open that door a little bit and walk through it. It was curiosity and hard work, and that led you down a path. It’s been true my entire career.”

Big Break

In 1984, Joyce was hired at KMGH-TV in Denver, and met her co-anchor of the afternoon news, Harry Smith. Two years later, they were married. Soon, Smith was hired by CBS News to work in either Dallas or Chicago. Joyce landed a job in Chicago but Smith was assigned to Dallas and Joyce followed. In the summer of 1986, she landed a gig at WFAA-TV in Dallas and Marty Haag, the news director there, took her, and sports, seriously. The latter was finally treated like news in a city with a bustling professional and college sports scene.

Joyce did features connected to different games, but her big break came in 1987. She was asked to do a live report for the Denver Nuggets vs. Dallas Mavericks game at Reunion Arena. The Nuggets head coach Doug Moe had long refused to talk with the station but Joyce had met Moe when she worked in Denver. So Joyce called the team’s hotel and the receptionist put her through to Moe’s room. She got her interview, and everything changed. Joyce became a full-time sports reporter at WFAA and its weekend sports anchor.

“Listen, I think I’m plenty smart,” Joyce says. “I’m not brilliant. I’m a pretty regular, average person. You learn [to ask yourself] ‘What if I called? I wonder if I can get him? What’s the worst thing that could happen?’”

Joyce worked harder than her counterparts. When she started covering the Dallas Cowboys during the notoriously dull NFL training camp, the more experienced reporters went golfing. Joyce never left — she didn’t want to miss anything. The coaches saw her commitment and started feeding her information.

She eventually won over Cowboys coach Tom Landry. After she sent questions into the locker room, Landry appeared in the hallway. He looked at Joyce, nodded, and opened the door — “Men, she’s coming in!” Joyce remembers him calling into the locker room.

The tests didn’t stop when she was hired by CBS Sports in 1989. At the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament, Joyce was assigned to cover regions featuring the University of Indiana, then coached by the volatile, controversial Bob Knight. Time and time again, it seemed Joyce had to interview Knight over some foible. Each time, it was like confronting a swarm of hornets. Again, Joyce had to interview Knight one-on-one after another headline-making act. The school’s ground rules: ask Knight about anything, except that.

Her producer disagreed and told her to make it the last question of the interview.

“I’m not going to do that. If I gave the [sports information director] my word, I’m not going to ask,” Joyce recalls telling her producer.

The next day, Bill Raftery, the legendary voice of men’s college basketball on CBS, approached Joyce: Knight wanted to see her. Joyce was petrified, so Raftery accompanied her to Indiana’s locker room.

Someone had overheard her hallway conversation and now Knight knew what she had told the producer. He told her that took a lot of integrity and honesty, “and you’re okay,” Joyce remembers him saying.

Later that day, at halftime of Indiana’s game, the coach was waiting for Joyce to do an interview. He was positively magnanimous.

Closing Ceremony

Joyce was inducted into the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame last December. And while she extensively covered tennis in her career, she is best known for working the Olympics. She co-hosted the opening and closing ceremony for the 1994 Lillehammer Winter Games and the 1998 Nagano Winter Games for CBS. For NBC, Joyce has covered several sports during the games, including figure skating, short track speed skating, gymnastics, and diving.

For the Paris games starting in late July, she’ll be serving as a sideline reporter for diving and filling in elsewhere as needed. She says that assignment is “so much fun, getting out and about and actually experiencing more of the Olympics.”

In late August, Joyce will return to Paris for the summer Paralympics where she’ll serve as a co-host from the USA House — a “home away from home” for athletes, coaches, families, and more during the games.

“Every time I do an event, I come home, and I’m just jazzed,” says Joyce about the games. “I’m excited for the next one.”

And while she expects this Olympic games to be her last, Joyce doesn’t expect to stop working. In April, she published a children’s book, “Legends of Women’s Gymnastics.”

“I’m not ready to rest,” Joyce says. “I know that the end is coming, but I don’t really look at it like that.”

Joyce doesn’t have to be on television anymore, but she still wants to be involved in it. She loves coaching and mentoring aspiring broadcasters. That’s what will make this year’s Paralympics so rewarding — she will work alongside a former Paralympian who wants to break into sports television.

That desire to pay it forward, Joyce says, is rooted in the community and “generosity of spirit” she encountered at U-M.

“I feel so indebted to the University,” she says. “My best friends are still my college best friends. I go back for games,” says Joyce, who attended the football national championship game in Houston. “It’s truly in my blood.”

Pete Croatto is a freelance writer based in Ithaca, New York.