Rajiv Shah, ’95, was sitting at a conference table at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle in 2002 when Bill Gates asked how much it would cost to vaccinate a single child. Gates was looking to find the cost of vaccinating every child in the world against preventable diseases.

“We didn’t call them big bets, but in retrospect, they were,” Shah says. “They were efforts to achieve massive, large-scale change, and they were grounded in the idea that we were trying to solve a problem in its entirety, as opposed to doing a little bit of charitable work and feeling that doing a little bit of good is good enough.”

Gates’ simple question sparked solutions through the foundation that accelerated the development and introduction of several new vaccines and led to the immunization of nearly 1 billion children over nearly 20 years through the foundation’s partnerships.

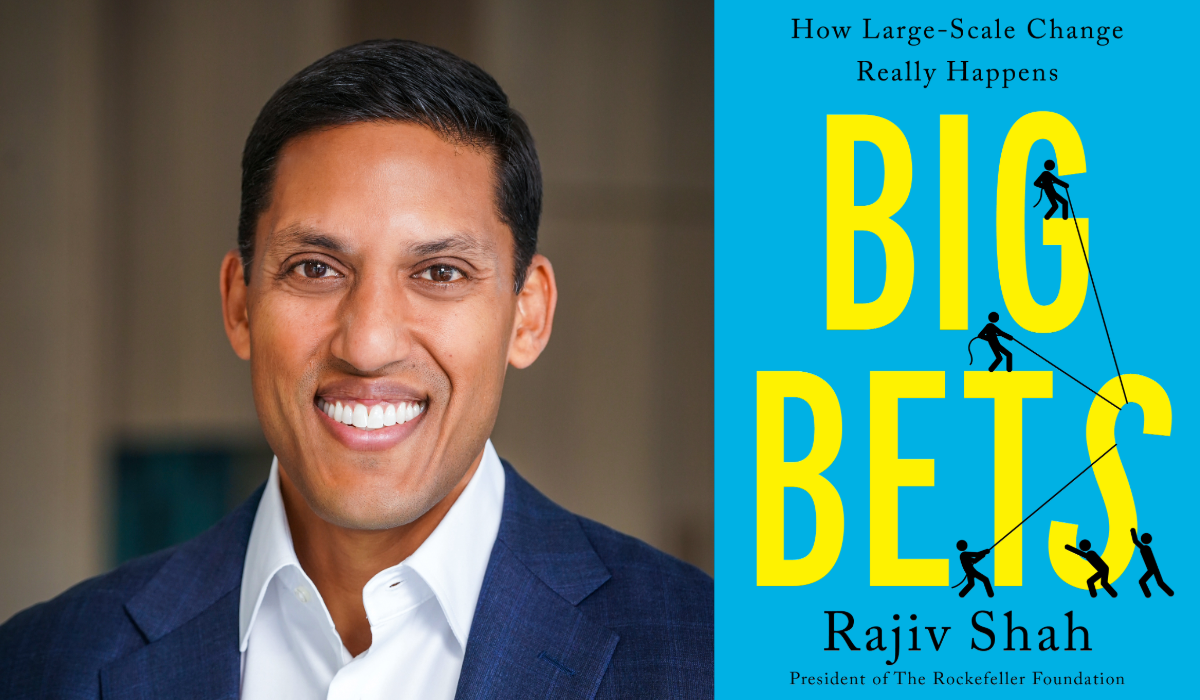

This is far from the only effort to create large-scale change that Shah has been a part of in his philanthropic career. Armed with an economics degree from the University of Michigan, and master’s and medical doctorate degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, Shah has worked on the 2000 Gore presidential campaign, held leadership positions at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, served as the 16th administrator of the United States Agency for International Development, and is now the president of The Rockefeller Foundation.

After a career of avoiding aspiration traps and taking big bets to solve global issues, including the West African Ebola pandemic, food security, and childhood immunizations, Shah is hoping to help leaders incite transformational change with his book “Big Bets: How Large-Scale Change Really Happens,” which hit shelves on Oct. 10.

Changing the World

“Big Bets” begins with the line: “If you’ve picked up this book, you’re drawn to the possibility of changing the world in a big, lasting way.”

Though he didn’t realize how pivotal it was at the time, this draw began for Shah when he was 17, watching Nelson Mandela on television while he was speaking in Detroit. He remembers Mandela ending his speech with a message of respect, admiration, and love for the people of Shah’s hometown.

“I just thought how incredible that somebody could be incarcerated for 27 years, go through his life experience, come out, and spread love and optimism and hope around the world and in my hometown. It was just a very special moment,” he says.

For Shah, optimism plays a significant role in transformational change. Staying optimistic when taking big bets can help leaders avoid what Shah calls “aspiration traps” — the overwhelm of a complex problem that can make “would-be world-changers” feel cynical, hopeless, or simply content with settling for “good enough.”

“It’s too easy to be influenced by what’s on social media or what’s in the news and believe that our politics are broken. Our corporate leaders are self-interested, primarily. Our world is hurtling towards a climate crisis that will just be hurtful to everybody. And I felt that in this moment, especially when I started writing the book during COVID, I felt like we needed a more clear view of how to be optimistic,” he says. “I wanted more people to believe that it is actually realistic to be optimistic about our future. That’s why I wrote the book.”

The Right Bet

There are three core elements of a big bet: having innovative solutions that can solve problems at scale; being able to build unlikely partnerships; and being able to measure results and track progress.

“When we make decisions [at The Rockefeller Foundation] about which big bets to pursue, we try to assess our likelihood of success on those three criteria. And that informs our decision-making,” Shah says.

Finding innovative and scalable solutions can take time, and Shah suggests readers start with simple questions, like the one Gates asked in 2002. Simple questions can also help avoid aspiration traps.

A big bet’s success relies on partnerships, and Shah encourages readers to be open to unexpected allies, be vulnerable, and find common ground before they need it.

“Every generation experiences what seems like a decay in our politics. And yet we still come together and get things done. And a lot of that, I think, is because human relationships are resilient. When you build them, they last, they matter, and they help you become even more effective at making big bets happen,” he says.

Shah’s next big bet is on climate change. In September, The Rockefeller Foundation pledged to invest more than $1 billion over the next five years to fight climate change.

The proceeds from “Big Bets” will go to The Rockefeller Foundation to support its “ongoing work to support big bets for humanity — and those who will lead them.”

Leaders and Best

The big bet mindset is how Shah imagines society will tackle some of the world’s most complex problems, but he says that one of the most important bets to take is the one on yourself.

“I’ve learned over time that big bets start with betting on yourself. But I didn’t know that at the time,” Shah says, recalling that he tried a lot of different things, “all of which were interesting, some of which worked and some of which failed.”

“I knew I had a passion for public service and social impact, but I didn’t really know how a young person com-ing out of Michigan and med school in Philadelphia at Penn makes that transition. It was just unknown to me.”

Shah says the key was finding mentors who understood his goals.

“I was fortunate to have mentors and, at the time, girlfriend, now wife, that knew what my aspirations were and encouraged me to take risks I probably wouldn’t have taken without their encouragement. And the lesson I learned from that is for young people in particular to find mentors who really can unlock your full potential and encourage you to take some of those risks early in your career that might otherwise be elusive,” he says.

Though his work has taken him all over the world, Shah stays connected to U-M and has served on the Alumni Association’s Board of Directors since 2020.

“I’ve always felt grateful for being part of the Michigan community. I think being a Wolverine was one of the highlights of my life. Getting to serve on the alumni board is a very special opportunity to give back. And it’s awesome to get to advance the mission of a great institution,” he says.

Shah says the skills students learn at U-M, especially to be proactive and find opportunities, help them thrive as alumni and can help them change the world.

“Especially for Michigan alumni, we’re already taught to be optimistic, to look for solutions or to invent them and to bring people together and to solve some of the world’s biggest problems,” Shah says. “Whether it’s climate change, which I know is very much the focus of student energy right now on campus, or the opportunity to build a more just and equitable society, there’s just no question that all of those things you learn on campus, you’ve got to keep fresh and you’ve got to keep with you as you as you grow your career, no matter what your career is.”

Katherine Fiorillo is the editor of Michigan Alum.