A Lifelong Educator

•

Photo courtesy of the bentley historical library

Sophia Holley Ellis, ’49, MS’50, MA’64, was used to being told “you can’t.” As a Black woman born in 1927 in Detroit, she was expected to sit quietly, go to school, get a factory job, find a husband, and start a family.

She was told she couldn’t learn German, she couldn’t go to college, she couldn’t move into the dormitories with the white girls, she couldn’t be a teacher…

Sophia died on Dec. 7 at the age of 95, after spending her career as an educator. For women like her, life was filled with closed doors. She made it her life’s mission to not only burst through those doors but hold them open for the students who came after her, all the while telling them “you can.”

You Can’t Learn That

When Sophia was a child, she was told that Black people couldn’t learn German.

“She would speak about the fact that the German intellectuals determined that because African Americans had smaller brains, they were not capable of learning such complex languages and being as smart,” Sophia’s niece, Millie Holley, recalls.

She was encouraged to pursue sciences by her mentor and godfather, Victor Julius Tulane, MS’29, PhD’33, who was studying chemistry at the University of Michigan.

“My god-father, studying German at the University of Michigan at the time encouraged me at about aged five to ‘start learning German right away’ if I wanted to become the great scientist that I had told him I would be,” Sophia writes in a handwritten autobiography about her love of learning and teaching, dated Dec. 8, 1987. “Taking him at his word I did just that. I listened to the German-American Hour on the radio and imitated the people there. I listened and imitated two German men who came to my neighborhood — one to collect rags and the other to teach violin and harmonica. (I learned to play the harmonica from him).”

German quickly became one of the great loves of her life, and she sought to learn more at every opportunity, even petitioning to change high schools to attend the one that taught German.

Based on where she lived, Sophia was supposed to attend Cooley High School, but the school wouldn’t accept a Black girl into the college preparatory courses so she transferred to Northern High School, her eye always on her ultimate goal of attending U-M.

Sophia graduated magna cum laude and earned the McGregor Fund Full Scholarship through the Urban League of Detroit and Southeast Michigan. Ready to live her dream, she matriculated to U-M in October 1945, arriving two days before classes began and ready to study German and biology. But Sophia found her move-in day experience was far different than the one most Wolverines have today.

Photo courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library.

You Can’t Live There

As a Black student, Sophia was told she couldn’t move into the mostly still-segregated dorms and, like other Black students, was encouraged to find a job as a live-in maid near campus. Sophia found a German family that lived on Geddes Ave. who let her live there as an in-home nanny while she was attending the University. The Roberts were German-Jewish refugees who kept in close contact with Sophia long after her graduation — Elsa Roberts, the child she cared for at only 18, attended her celebration of life in January.

Robert Shedd, Sophia’s English teacher, saw her brilliance and potential and demanded she be allowed to move on campus to live in the University’s first cooperative dormitory, the Mary Markley House.

There, Sophia made lifelong friends, studied, danced ballet, and joined student organizations like the German Club. But Sophia wasn’t readily accepted by her University peers.

“I’ll have to say it the way she said it: ‘I was at the University of Michigan, but I wasn’t like all of the Black students.’ She went to the University of Michigan to study, not to socialize. Not to dance or party,” Melvin Holley, Sophia’s brother, recalls.

“She knew struggle,” he says.

You Can’t Be That

After graduating from U-M in 1949 with a double major in biology and German and qualifying teaching certificates, Sophia was told she couldn’t be a teacher.

“When I attempted to obtain a job I was turned down innumerable times — all because of my indelible skin color,” Sophia writes.

She took jobs as a store clerk and a nightclub dancer, until her scholarship advisor, also the assistant superintendent of Detroit Public Schools at the time, called her family and was “enraged,” according to Sophia, to learn Sophia’s applications had been allegedly “lost” for the past several years. 15 minutes later, she had a job offer.

However, the job search wouldn’t be the last time she was overlooked. On her first day at Commerce High School in 1957, the principal assumed she was the new cleaning woman and reprimanded her.

“He treated me harshly by demanding that I ‘sit over there’ because I was too early to come to work. I sat there for a split second. When he disappeared so did I — found the science room without a teacher and introduced myself to the students,” Sophia writes.

Friends, family, and former students remember Sophia stated that she believed Black people aren’t discriminated against because they’re Black; they’re discriminated against because others are ignorant. And she never let others’ ignorance stop her from pursuing a lifelong career of teaching.

“Without any reservations I can truthfully admit that I love teaching,” she writes in papers that are kept at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. “It thrills me to watch people learn and show their satisfaction in modifications in their behavior as a result of something they have learned. Monetary compensation for my teaching services cannot be even closely equated with the personal satisfaction I have been afforded by knowing that I have been instrumental in bringing about positive changes in the lives of hundreds of people.”

You Can Do Anything

Sophia was always determined to pave the way for Black students’ education, even when the school systems were not.

“Imagine being a young child, hearing ‘you’re not going to be smart.’ And it’s still going on here today in Detroit,” Millie says.

Even in her first job as an elementary school science teacher, she found ways to support Black students’ success.

“I refused to place pictures of Caucasians on my bulletin boards because my pupils were all black. (I colored Caucasian faces brown and the hair black.) I refused to place pictures on bulletin boards of situations that I felt were foreign or unattainable to my black children,” Sophia writes.

She continued to advocate for her students and Black students everywhere to have equal opportunities and access to education.

In the 1960s, while studying for her second master’s degree at U-M, Sophia helped form the Black Leadership Council and served as a residence counselor in Mary Markley Hall — all part of the University’s commitment to increase Black student enrollment.

While teaching at the High School of Commerce, the school chose to not teach achieving Black students about studying business at the college level, so Sophia began to organize trips to U-M for the students herself.

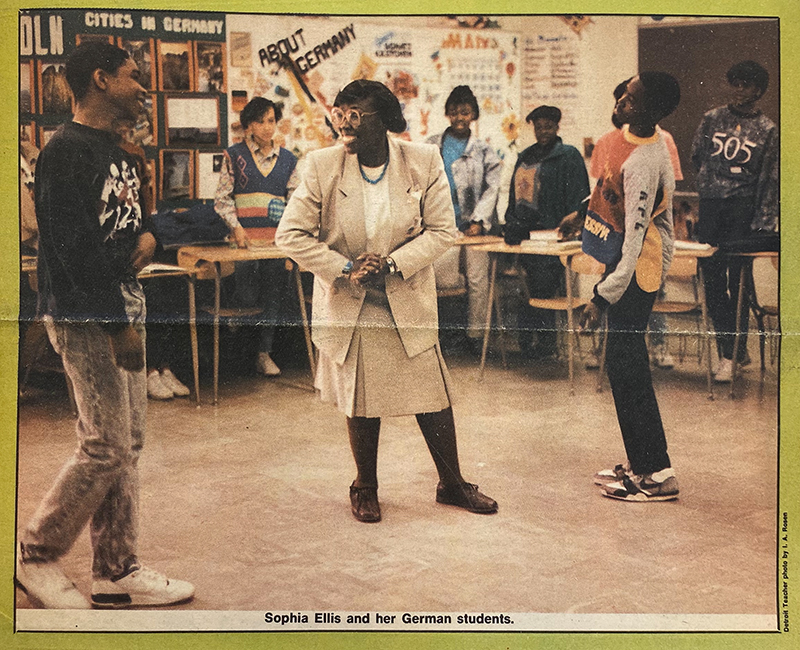

As a German high school teacher, she made a poster that read “German is for all” in English and German, with pictures of her Black students learning and celebrating German culture adorning the sides. The poster became so celebrated, it was written about in a German newspaper.

Sophia not only dedicated her life to learning; she dedicated her life to creating opportunities for Black students that didn’t exist for her.

She Did It All

Outside of the classroom, Sophia traveled the world, played the harmonica, danced all through her life, and enjoyed rich relationships with friends and family.

Over her 56 years in teaching, she earned incredible achievements including the prestigious Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Detroit Teacher of the Year, the Goethe-Institut/American Association of Teachers of German Certificate of Merit, and the National Council for International Visitors’ Phyllis Layton Perry Educator of the Year award, amongst many other accolades and recognitions.

A letter explaining why she should be considered for the Leonard F. Sain Esteemed Alumni Award reads: “Personally, Sophia has witnessed many fundamental changes in black culture and has served as a catalyst for many of them.”

In 2009, Sophia established a scholarship fund at the School of Literature, Science, and the Arts with an endowment of $25,000. The scholarship prioritizes students from Detroit and has been helping students since 2011, though Sophia privately funded several students’ education long before a scholarship boasted her name, even as a Detroit public school teacher earning a modest salary.

Now, in her memory, there’s also a Victor J. Tulane LEAD Scholarship at the Alumni Association, honoring the mentor that encouraged her to pursue a life of education when so many others told her she couldn’t.

“The Sophia Holley [Ellis] scholarships at LSA and the Alumni Association are also critical aspects of her legacy because, perhaps of all her roles in life, ‘teacher’ and ‘mentor’ may well be the most significant in terms of their impact on other people,” Michael Mullett, ’66, MA’73, a close friend who helped establish the LEAD fund in her honor, says.

The legacy Sophia leaves behind is one of pure perseverance in the face of adversity, the lesson to her thousands of students that they can achieve anything, even when everyone is telling them they can’t.

Her family and friends remember her for her brilliance, her “bling,” and her love of education — all things that, as they lovingly say, are “so Sophia!”

KATHERINE FIORILLO is the editor of the Michigan Alum.