The historic Tappan Oak was an icon for generations of University of Michigan students and community members, situated in its centuries-old home next to the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library.

“Its original location was a popular place for students to congregate between classes, sit in the grass under its large canopy. It was also a wayfinding point for people to navigate campus,” said Mike Rutkofske, U-M’s campus forester.

One of about 17,000 inventoried trees on campus, the Tappan Oak was named after former President Henry Tappan by the graduating class of 1858. It was a native Michigan species called a bur oak and was one of the largest trees on the Diag, measuring 50 inches in diameter, towering at 80 feet high, and reaching about 90 feet across with its branches.

The tree was removed in November 2021 due to decay and root fungus. After removal, it was determined that the Tappan Oak may have dated back to 1710.

Wood from the Tappan Oak has been put to good use. Students from the School of Literature, Science, and the Arts used pieces to make tables. At the School of Environment and Sustainability, the stump was used for student research.

And as Rutofske was sorting through requests of different people who wanted a piece of the Tappan Oak, he received a phone call from Chayce Griffith, ’16, who informed him that he’d been growing seedlings from the historic tree.

“My jaw dropped,” Rutkofske said.

Griffith dreamed of attending U-M while growing up in Saline, but he struggled to make meaning of his time on campus and, as a sophomore, collected acorns from under the Tappan Oak.

“I was trying to take something of [the University] with me to have some sort of evidence that I was actually here, because I didn’t feel like I was making a mark at all,” Griffith said.

According to a 2021 article in Michigan Today, Griffith Googled how to grow a tree from an acorn, put about 20 in styrofoam cups, added potting soil, and placed them in his parent’s garage fridge.

Now, one of those seedlings, a direct descendant of the historic Tappan Oak, has a new home next to the Alumni Center, between the Alumni Association’s building and the Michigan League.

“In all of this, I want it to be remembered that all that I actually did was stuff some acorns in my backpack and then plant the acorns,” Griffith said. “I didn’t know what the Tappan Oak was at the time — it was just the biggest tree around. That’s why I grabbed the acorns from the base of that tree in particular. But walking by it multiple times a day, it was special to me, the Tappan Oak. I just didn’t know it was so special to so many other people as well.”

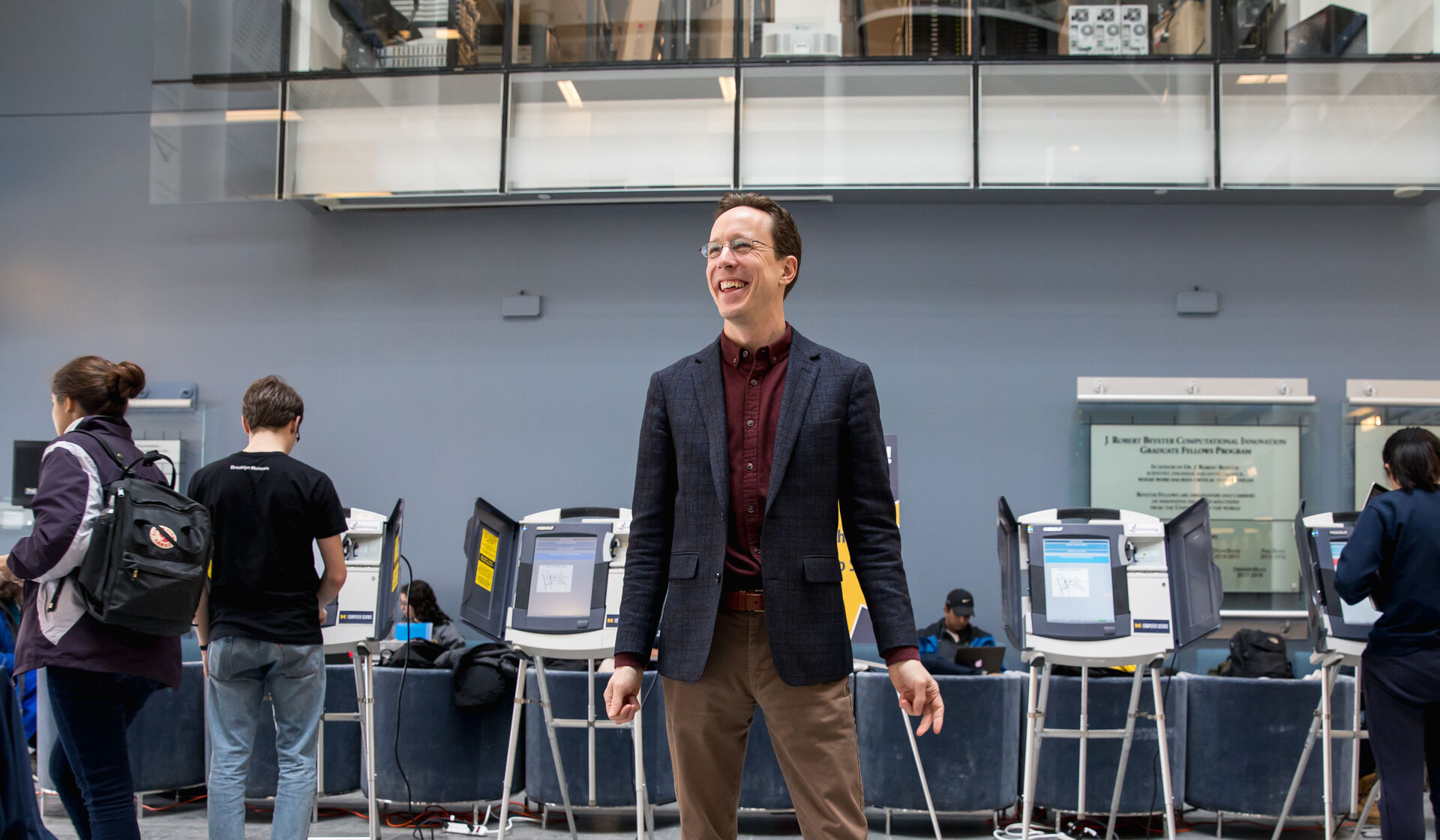

Griffith returned to campus with his family on April 22 — Earth Day — to plant the Tappan Oak’s daughter in a small ceremony outside the Alumni Center.

“We would not be here without Chayce’s horticultural curiosity, his efforts aligned with the University of Michigan’s commitment to campus sustainability, and environmental stewardship,” Rutkofske said.

Griffith is currently pursuing his Ph.D. at Michigan State University, where he is studying trees (albeit, apple trees).

Griffith took a moment during his remarks to reflect on the University’s recent decision to close the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

“At the time that I originally took those acorns, I felt like I was letting the University down. But now, coming back here in 2025, I think the University is letting me down . . . In high school, I remember having to memorize Supreme Court cases where the University was sued for trying to support equity in bringing in new students, but now the word equity has become a dirty word, and the University has given up without a fight. And that wasn’t the Michigan that I knew,” Griffith said.

Griffith recognized the “lovely” sentimental nature of the tree planting ceremony while calling upon the University “to live up to its own name in history.”

“The Tappan Oak is older than the nation itself, and it watched as the world transformed around it and, thanks to the good people here, its daughter is going to get a leg up on living the exact same life span or maybe even longer. And so it’ll watch as the world keeps changing. And my life and all of our lives are going to be just a fraction of the story of this tree,” Griffith said. “And this time that we’re in now — this phase, these years — this phase will be a blip in its history, and someone will have to squint to even find those rings in its wood, but they’ll be there.”

Katherine Fiorillo is the editor of Michigan Alum.