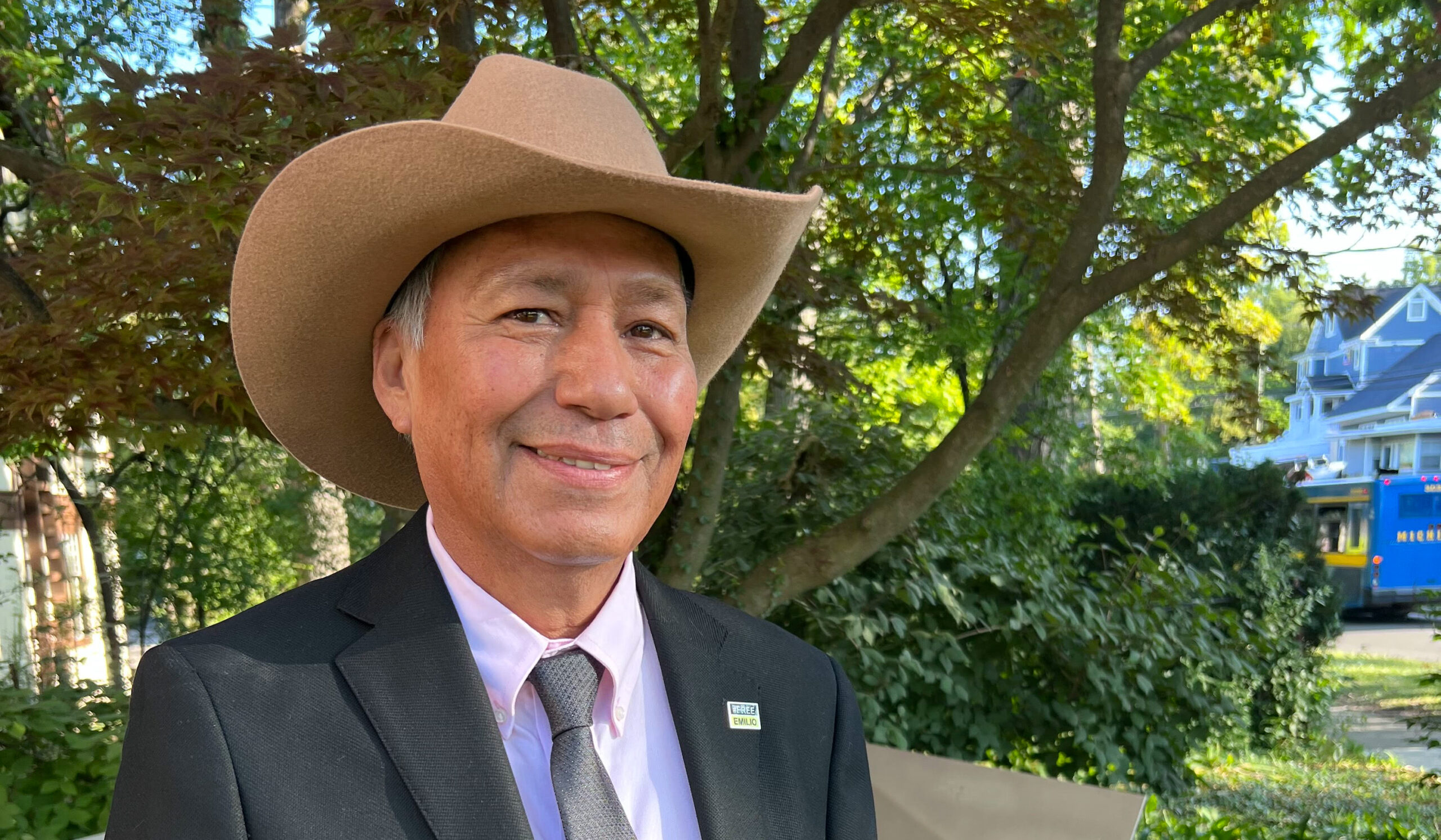

Lynette Clemetson remembers driving frantically to a farm in Dexter, Michigan, where Emilio Gutiérrez Soto was working. She’d just been handed news for which they’d been waiting years, but with no reception on the farm, Gutiérrez didn’t know it yet.

So Clemetson, the director of U-M’s long-running Knight-Wallace Fellowship program for professional journalists, went to deliver the news herself.

She pulled up to the farm where Gutiérrez was tending to the roosters and ran up to share the call she’d just received from his lawyer: after 15 years of immigration court, he had finally been cleared for asylum in the United States.

“I heard the news from Lynette, but I didn’t believe it,” Gutiérrez said. “‘You won,’ she said. ‘I won what?’ I asked. ‘Your asylum!’ she says. I just said, ‘Thank God.’

“I still haven’t accepted that this is reality.”

Gutiérrez and his son, Oscar, had been stuck in legal limbo since 2008, when they first pleaded asylum at the border after the Mexican army began threatening Gutiérrez for writing articles exposing corruption in the northern region of Chihuahua.

But instead of being processed as political refugees, they were forced in and out of immigrant detention centers, which is where Gutiérrez was in the spring of 2018 when Clemetson first met him and offered him the chance to move to Ann Arbor as a Knight-Wallace Fellow.

The fellowship brings working journalists to Ann Arbor for an academic year to take classes and engage in research projects. For Gutiérrez, it also brought him far away from the dangers of the border and connected him with legal and diplomatic resources — including U.S. Representatives Debbie Dingell (D-MI) and Fred Upton, ’75 (R-MI) — who could help fight for his case. The Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, who spent more than a year in Iranian captivity, visited campus to present him with a press freedom award at the Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre.

Other U-M departments got involved, as well. When Gutiérrez’s judge refused to accept his archive of newspaper articles as evidence to demonstrate he was a journalist because they were in Spanish, dozens of student volunteers at U-M’s Language Resource Center worked around the clock to translate his stories into English before a crucial court deadline.

And U-M alumni gave him a job. Through a connection from University Musical Society president emeritus Ken Fisher, ’71, Gutiérrez was connected to Argus Farm Stop owners Kathy Sample, MBA’89, and Bill Brinkerhoff, ’87, MSE’89, MBA’89, as soon as his fellowship ended. The couple had recently opened their Dexter farm, and Gutiérrez had farming experience. He agreed to work on the farm while he waited for his case to process, finding the crops and livestock to be a comforting environment.

In the meantime, his son worked at Zingerman’s.

“The community has always been generous with me — very, very generous,” Gutiérrez said. “This is my new home, in Ann Arbor.”

Yet despite the groundswell of support for Gutiérrez’s case at U-M, it was unclear whether it would make a difference in the end. The same judge in El Paso, Texas, twice ruled he should be deported, with the second ruling coming as Gutiérrez’s fellowship was ending.

It wasn’t until September 2023, when a three-judge panel on the appeals court ruled that the first judge’s claims were “clearly erroneous” and that Gutiérrez was, indeed, a suitable candidate for asylum, that a new reality could finally unfold for him and his team.

As the U-M community celebrates Gutiérrez’s newfound freedom and the journalist ponders his next moves, the Knight-Wallace program is doubling down on its commitment to press freedom. Its 2023-24 class includes journalists from Hong Kong, Ukraine, Afghanistan and Haiti, who have faced persecution, censorship, and even an assassination attempt.

Clemetson believes that U-M’s program has a clear role to play in cases like Gutiérrez’s.

“It is something to celebrate,” she said. “But I also think we all want to spend time focusing on the lessons of this case, and the policy implications of the case, to make sure we can do something so that other journalists who are in danger don’t have to go through this.”

Fighting for Gutiérrez, Clemetson said, crystallized the fellowship’s mission for her.

“Yes, we want to offer a lifeline to the journalist,” she said. “But we’re not just trying to save the journalist. We’re trying to save the journalism.”

Read more about Gutiérrez’s story in “Seeking Asylum in Ann Arbor,” published by Michigan Alum in Spring 2019.

Andrew Lapin, ’11, is a journalist with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and the host and creator of the podcast “Radioactive: The Father Coughlin Story” from Tablet Studios and Exploring Hate. He is also a RIAS Berlin Journalism Fellow.

He received translation assistance on this story from Michele Salcedo.