The Fight for Equality on the Athletic Field

•

Mary Forrestel Borden, ’75, grew up in a small town east of Buffalo, New York. But Maize and Blue have run in her family for generations.

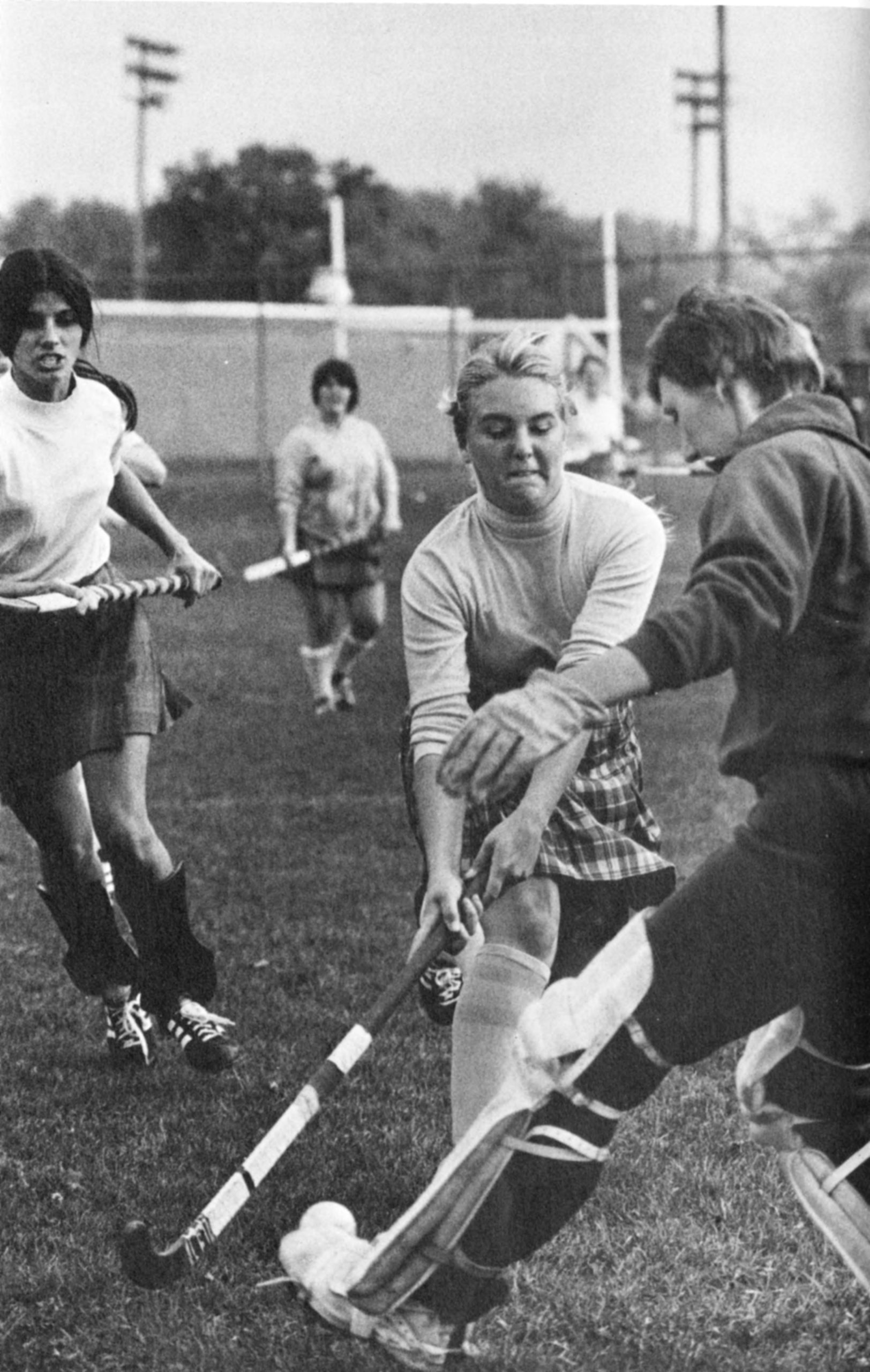

Her parents and grandparents went to U-M, and eventually, she and six of her 10 brothers and sisters would, too. So Borden, a member of U-M’s first varsity field hockey team, knew that playing in the Big House was a special thing — even when the stands held only one fan.

“My brother Peter was a year ahead of me at Michigan, and he knew all of us on the team,” Borden, then known as Mary Forrestel, remembers. Home games took place in Michigan Stadium early on fall semester Saturdays, with tape marking off field hockey lines on the football field. The stands were usually empty, but one morning Peter Forrestel, ’74, MS’75, showed up to support his sister with enough enthusiasm to make up for the sparse attendance.

“He took a construction cone and went up to the top row and was hollering to us as if it was a megaphone,” Borden says, laughing. “There we are in the Big House with one fan — and then advance to four hours later in that afternoon, when we had a Michigan football game with over 100,000 fans. So the dichotomy was pretty striking!”

Looking back, the experience feels a bit surreal, but it was typical of the years before and right after the passage of Title IX, the 1972 federal law that prohibits education programs from discriminating on the basis of sex. Part of a legislative package known as the Education Amendments of 1972, the law applies to any educational institution that receives federal funding, and it doesn’t explicitly refer to sports. Still, it is in college athletics that Title IX has had the clearest impact — one that’s felt 50 years later.

“After Title IX, people started saying, ‘Hey, you know, athletics is a part of education,'” says Ketra Armstrong, a professor of sport management at the School of Kinesiology and former president of the National Association for Girls and Women in Sports. “We saw marketing dollars, we saw scholarships, and participation rates soared exponentially. We had more girls or women playing sports, and there was new cultural legitimacy. Title IX legitimized the desire of girls and women to be in sports, which had always been perceived to be in the male domain.”

Of course, Title IX did not change perceptions overnight. That would still take a fight — one that alumnae who played for U-M during Title IX’s early years now recall with pride.

ON THEIR OWN

By the time President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law in the summer before Sheryl Szady’s junior year, the three-sport athlete from Grosse Pointe Woods, Michigan, was anxious for a fairer deal. While they routinely played varsity squads from other schools, women’s teams were officially club sports-level at U-M. That meant the athletes had to do everything themselves — from seeking a volunteer coach and scheduling practice time to washing their own uniforms and carpooling to games all over the state.

“We were selling apples at football games,” recalls Szady ’74, MA’75, PhD’87, who was manager of her field hockey team. “We’d sit down at the beginning of the season and say, ‘Okay, everybody needs to pay $20 to cover our expenses for the officials and the little Cokes and chips we would have afterward with the other team.’ So everybody would ante up, and then when you hopped in a car you were expected to give the driver $1 or $2 for gas. I was trying to figure out better ways of doing things.”

Title IX had just passed, but it wasn’t immediately clear how or whether it might apply to athletics. At first, officials interpreted it as targeting things like graduate and medical school applications and academic scholarships.

“There’s no guidelines yet, so you can’t say, ‘We’re suing the University for non-compliance,'” Szady says. “There’s equal something, but [athletics] was not even a topic of conversation yet.”

Szady started small, trying to get the Office of Development to add women’s athletics as a potential target for donors’ gifts. A series of meetings with administrators led to a chance to speak — for just five minutes — at a meeting of the board of regents. Szady and basketball manager Linda Laird, ’74, gave it their all.

Their appeal prompted U-M President Robben Fleming to appoint a committee that would study women’s intercollegiate athletics. Meanwhile, the implications of Title IX were becoming apparent. In August 1973, Ann Arbor activist Marcia Federbush filed the first-ever Title IX complaint against any university, alleging that the difference in U-M’s budget for men’s and women’s sports — $2.6 million versus $0 during the previous school year — amounted to illegal discrimination.

The summer before Szady’s senior year, six women’s club teams were elevated to the varsity level. But the victory wasn’t quite complete. Competitive schedules remained limited to Michigan opponents, and while the University provided women’s teams with vans to travel to away games, they often required a team member to drive. Dinner per diems were provided for away games, but the $3.50 barely bought the hamburger special at Big Boy’s with a piece of pie for dessert; the home game per diem was $1.50. There were no athletic trainers or sports information resources assigned to the six women’s teams. Practice gear was not provided, and game uniforms were distributed for the season to team members, who were responsible for individually laundering them for games. There were no team locker rooms available. Athletes came dressed in their own gear to practices and returned home to shower.

“Some things got better,” says Szady, “but for a long time, the women were traveling in vans when the men were flying or taking buses.”

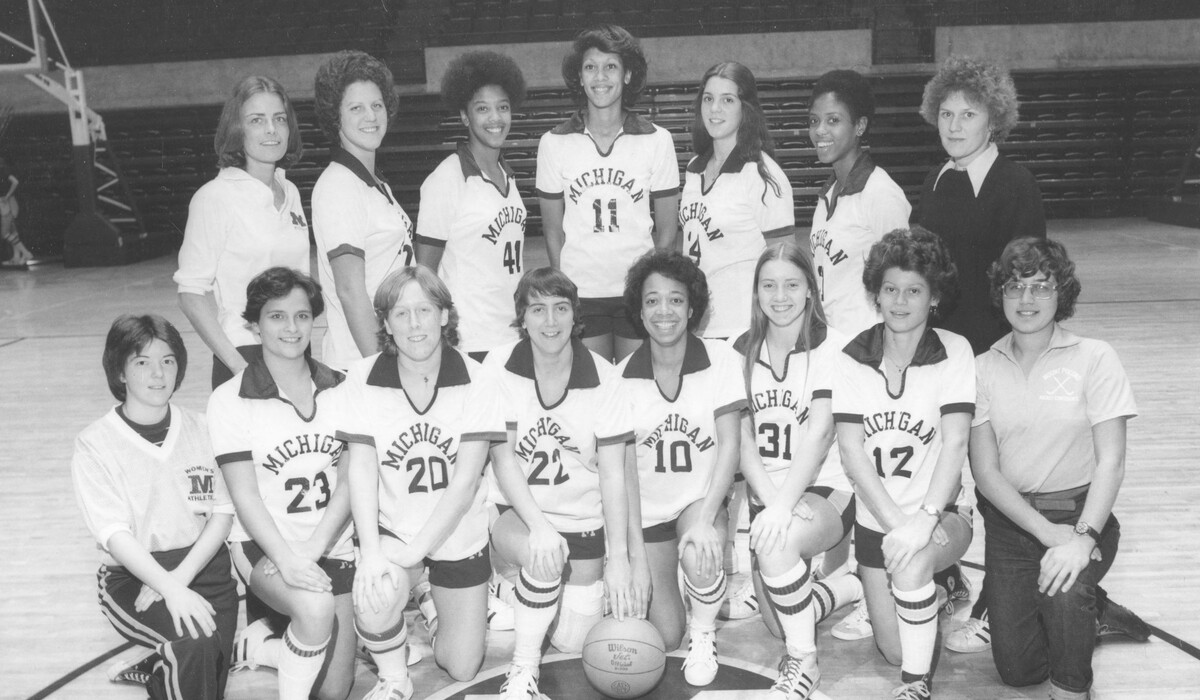

For Lydia Sims, ’77, a Detroit native who had been captain of her basketball team at Cass Tech High School, change came too slowly. During her first basketball season at U-M, she averaged 20 points a game, but the team’s record was 3-7. Sims soon realized they were hampered by inadequate facilities.

“We had tryouts and most of our practices in Barbour Gym, which was the girls’ gym,” Sims remembers. “It wasn’t a regulation-size basketball floor. They had a track that ran around the top of the gym, and if you shot the ball from certain parts of the gym, it would block your shot.”

Frustrated, Sims transferred to Immaculata College, a small women’s school outside Philadelphia that happened to have the top-ranked women’s basketball team in the country. During Immaculata’s 1974-75 season, Sims got the opportunity to play at Madison Square Garden in the first women’s basketball game ever shown on national TV. The recognition was gratifying, but in the end, Sims decided she still wanted a U-M education, so she transferred back for her junior year.

“As other schools started having good girls’ teams, Michigan was slowly catching up,” she says. “But we didn’t have a locker room. There was no such thing as a coach’s office. We took our own uniforms home and washed them and brought them back for the game. It was very grassroots.”

As a senior, Sims earned one of the first women’s basketball scholarships. Worth $526, it was exactly enough to cover the cost of one semester’s in-state tuition.

Photo courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library.

GAINS, CHALLENGES

Photo by the U-M News and Information Service.

In 1977, U-M appointed Phyllis Ocker, then a professor in the School of Education and a field hockey coach, as the first associate director of women’s athletics. By the time she retired in 1990, her budget had increased from $100,000 to $2.4 million; today, according to U-M’s report to the U.S. Department of Education, spending on women’s athletics totals nearly $25.4 million. The budget for women’s athletic scholarships is now $12.2 million (compared to men’s $15.4 million), and as of spring 2022 there were 414 women athletes with a total of 500 participation slots, along with 476 men with a total of 550 roster spots.

Michigan has seen a lot of progress, but there is still much to be done, says Armstrong, who in 2019 was appointed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to the Michigan Task Force on Women in Sports, which was timed to mark Title IX’s 50th anniversary. In June, the task force released a report calling for better enforcement and accountability of Title IX’s demand for equity, including through a required certification process, spot checks, and regular audits.

But as much as Title IX has been a game changer for women in sports, Armstrong says, there have also been unintended consequences that, she hopes, will one day be addressed as well.

“Title IX increased girls’ and women’s participation in sports, but it also created a very competitive model,” Armstrong explains. “New opportunities brought new pressures. And as women’s sports started to grow in popularity — more scholarships, more media attention, more marketing dollars — it attracted more men, and consequently also offered men more opportunities to be at the helm of women’s sports. When we saw women’s sports merge with men’s athletic departments, women lost the majority of the coaching and administrative opportunities. The range of leadership opportunities women lost in sports has yet to be regained.”

Even today, she notes, fewer than half of the coaches of women’s teams are themselves women.

The true realization of Title IX’s potential will come, Armstrong says, when top schools have women athletic directors — and when that development is no longer seen as newsworthy.

“Title IX says there shouldn’t be discrimination based on sex, but we know that the positions are gendered,” Armstrong says. “We know that the pay is gendered. We know that promotions are gendered. All of these things are gendered in a way that that celebrates men and challenges women.”

DEVELOPING LIFE SKILLS

When Mary Forrestel Borden’s younger sisters arrived at U-M after she graduated in 1975, they had a very different experience. There were more scholarships available for women athletes then, and the younger Forrestel girls, one a gymnast and the other two field hockey players, took advantage.

“That was unheard of, obviously, in 1972,” Borden says. “But somebody had to take the first steps to get the journey started. The inequity was stark, but they were making progress and developing opportunities. And the good news was, we had some pioneers at Michigan.”

After U-M, Borden returned to Akron, New York, where she has spent the last 47 years teaching middle school math and coaching field hockey, swimming, and track. Sports remain central to her life, and she still feels strongly that every girl and woman should be encouraged to pursue her athletic potential, wherever that may lie.

“Athletics is probably more important than academics in terms of promoting leadership and life skills,” Borden asserts. “To women, especially, the skillset you develop through the social and emotional journey in athletics is what builds women to be stronger leaders in every avenue.”

That has been Lydia Sims’ experience as well. After graduation, she took a job as the first assistant women’s basketball coach at the University of Detroit. During her three-year tenure, the Titans finished with a 68-15 record.

Looking back, Sims says it’s gratifying to think about how many people have benefited from Title IX, including her teammates, her University of Detroit players, and generations of girls and women around the country.

“We’re able to recognize everyone’s gifts,” Sims says. “We all have gifts, and Title IX allows the gifts to come forward.”

In 1980, Sims left Detroit to enroll in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, eventually becoming an obstetrician-gynecologist, a specialty she chose because she wanted to continue focusing on women. While she last stepped on the court in her early 30s, her years playing basketball had a life-long impact.

“It’s the major influence,” she says. “You learn how to compete, how to work toward a goal with others, how to accept defeat, how to accept winning. I know what I can do. I enjoyed every bit of it, and if I could be 19 again, I would!”

AMY CRAWFORD is a writer living in Ann Arbor.